Here’s the StFX News article on all of Lexy’s recent success.

Here’s the StFX News article on all of Lexy’s recent success.

Along with getting this year’s cover image for CJZ, Lexy has another photo competing for this year’s Science Exposed prize from NSERC. Vote for her photo here!

Here’s the details:

The observation of a seemingly simple feeding event can provide new insights into how sea slugs navigate changing ocean conditions. Pictured here is the sea slug Hermissenda crassicornis on an orange cup coral, with visible damage exposing the coral’s white skeleton. These slugs were previously thought to feed mostly on hydroids (small marine animals related to jellyfish), but my research suggests they may actually prefer orange cup coral, as shown here. This discovery is part of our work to understand how these sea slugs find food in environments with variable tidal flow and strong wave action, which can disrupt the odor plumes they might otherwise follow. While at the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre on the West Coast of Canada, we took some video recordings of these slugs in their natural habitat. By analyzing these recordings, we are uncovering new behavioural patterns that may help explain how they successfully forage in such dynamic ocean conditions.

Yet more congratulations to announce! Tanya O’Reilly successfully defended her MSc thesis today: Ribbed Mussel (Geukensia demissa) Demographics and Interactions with Cord Grass (Sporobolus alterniflorus) in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence, Nova Scotia. Tanya studied the ribbed mussels in salt marshes along the Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence. She found evidence suggesting substantial population declines over the last decade or more, likely linked to sea level rise and erosion of the seaward edges of the marshes. Western populations were faring much better than eastern populations. A fantastic achievement, Tanya!

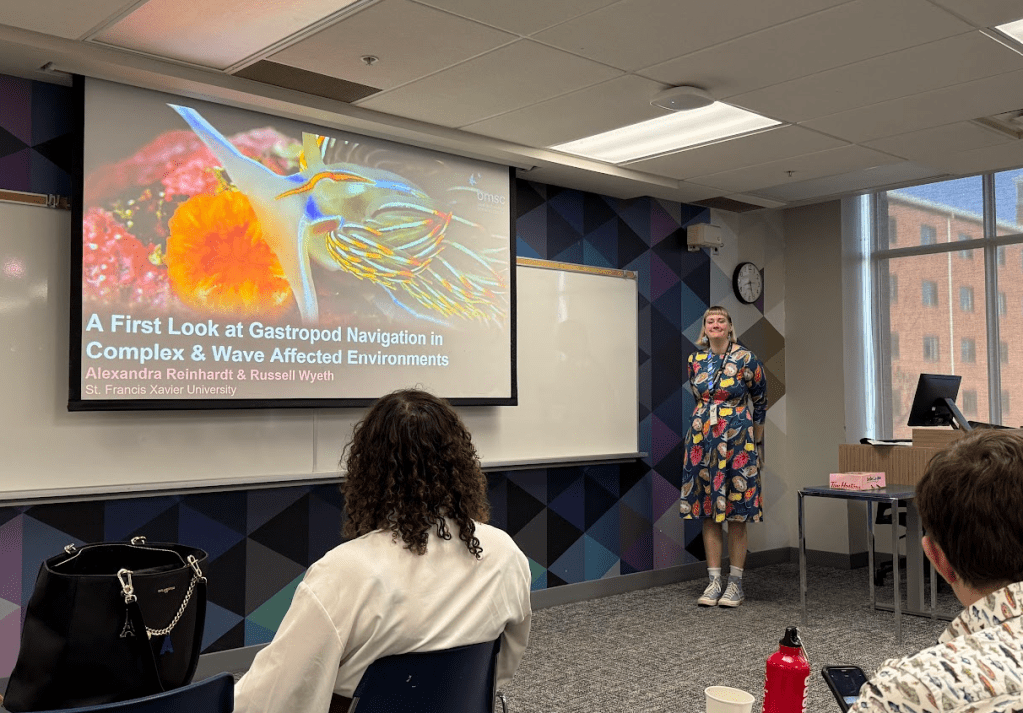

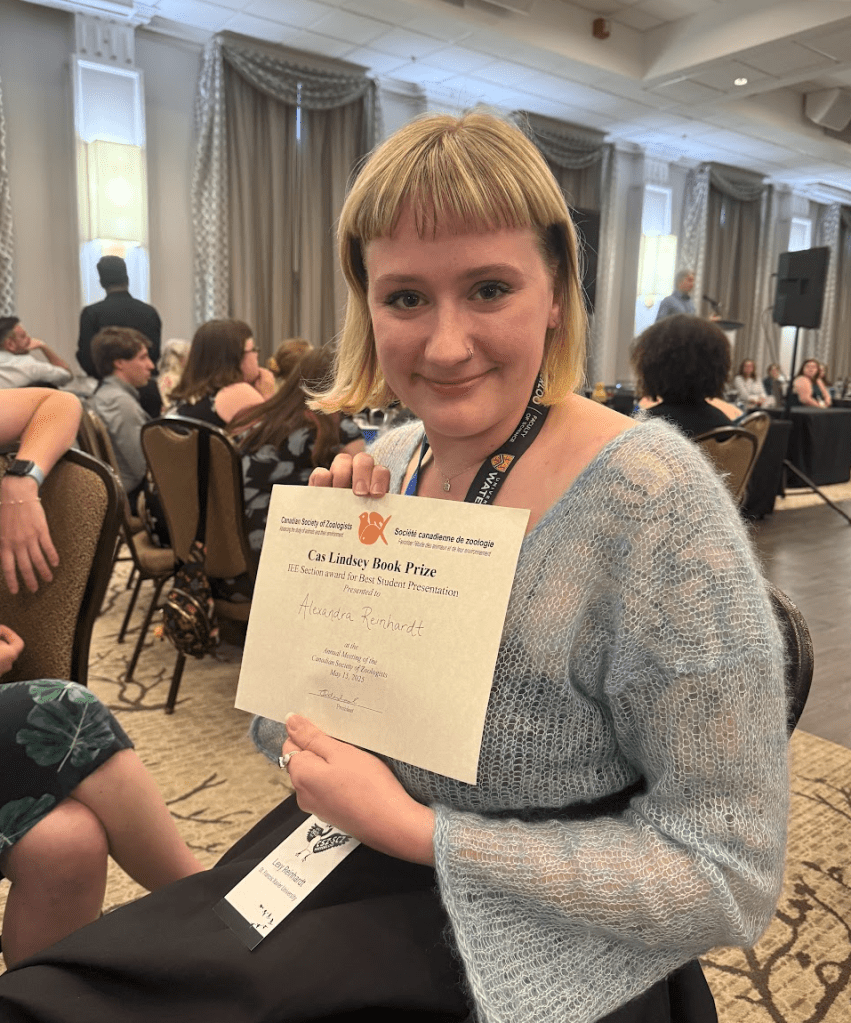

Two students presented this year at the Canadian Society of Zoologists annual meeting, which was its usual mix of great science and great fun.

Victoria presented her Honours thesis work (with help from Yulia) on snail neuroanatomy: Unravelling neuroanatomical complexities: Discrepancies in the labelling of octopaminergic markers in the nervous system of Lymnaea stagnalis. She did a fantastic job as the sole undergraduate competitor for the Hall Award for best student presentation in the disciplines of comparative morphology, development and biomechanics.

And Lexy presented the first analyses of her MSc project. She is studying nudibranch navigation using data collected on Hermissenda last summer at Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre: A first look at gastropod navigation in complex wave affected environments. She did even better, winning the CAS Lindsay Prize for best student presentation or poster in the fields of behaviour, ecology or evolution!!!

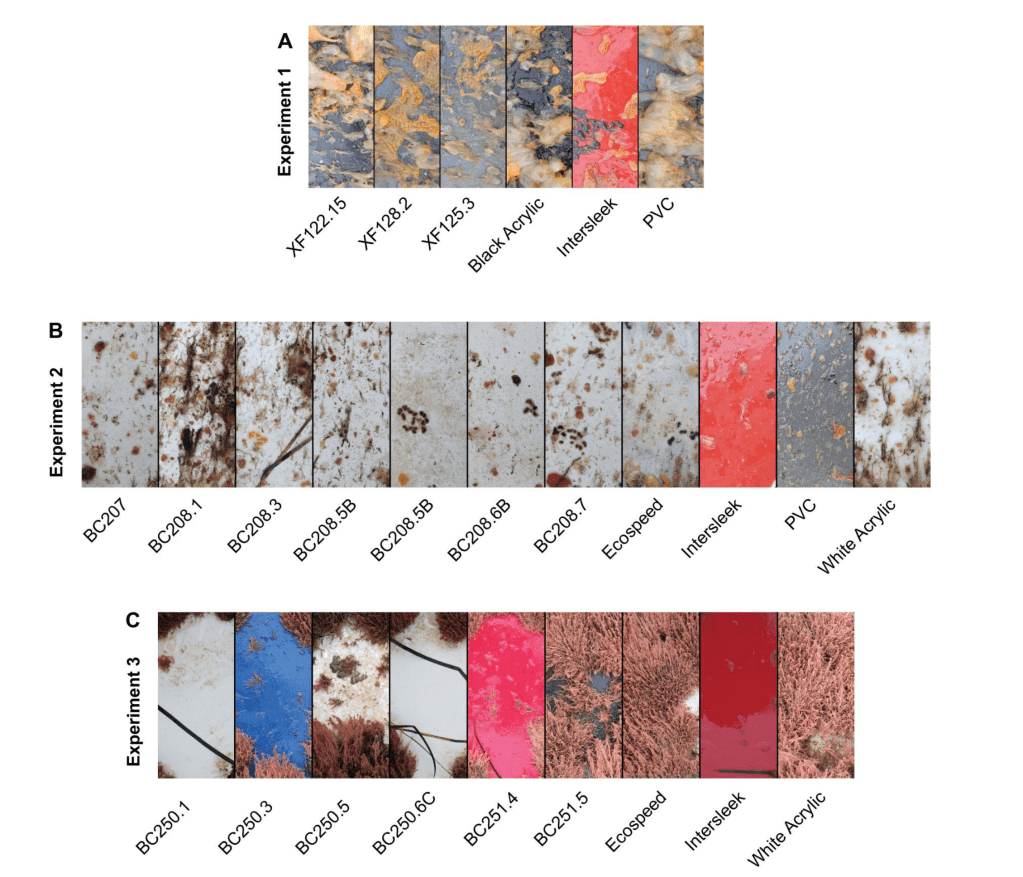

Special congrats to Ally Hunter who led the effort to get this study published. The experiments were spread over three years, conducted by the biofouling group, including contributions from Ally, Aaron, Kristyn, Kylie, Katherine, and Lexie. We field tested prototype coatings developed by our collaborator, GIT Coatings, Inc., and showed that by the final year, the coatings were able to reduce development of biofouling. The antifouling effect is probably based on making the coating surface slippery, making them much easier to clean off than uncoated surfaces. Such “fouling-release” coatings are a standard modern approach to producing an antifouling coating with lower environmental impacts. What makes the GIT coatings special is that they have higher hardness than typical, making them likely to be more durable than the relatively soft current fouling-release coatings on the market. In fact, our study is (we believe) the first study to document development of a hard fouling-release coating.

Hunter, A.T., Cogger, A.J., Boutilier, K., Curnew, K.H., Purvis, K., Trevors, A., and Wyeth, R.C. 2025. Development of marine antifouling performance in hard fouling-release coatings. Biofouling. Taylor & Francis. Available from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08927014.2025.2498027 [accessed 7 May 2025]. Alternate link for PDF access.

Our first lab meeting of the summer research season was an opportunity for a full lab photo…

Standing left to right: Ryan, Liam, Payton, Mike, James, Lexy

Kneeling left to right: Tia, Aidan, and Lauren

Background: courtesy of Aidan, and AI generated version of RCW with mimic octopus colouration!

Congratulations to Aidan McGowan who graduated with his BSc in Biology this past weekend! Although courses are done, he’ll be sticking around to work on the juvenile lobster research project for the next 8 months (at least!)

MSc student Lexy Reinhardt, who is studying navigation behaviour in Hermissenda, is also an avid naturalist. One of her many spectacular images of marine invertebrates has been chosen as the 2025 cover art for Canadian Journal of Zoology.

Not everyone made it, but those that did had fun! Cheers to Tia, Lexy, James, Ryan, Aidan and Lauren

Kudos to the awesome undergraduate students who have been sharing our work recently! At Science Atlantic, Aidan McGowan presented some of the collective work of the lobster group on how lobsters respond to different portions and preparations of bait (lobsters aren’t picky). At Student Research Day, Tia Landry presented on the biofouling group‘s initial explorations of how the susceptibility of biofilms to ultraviolet light varies with time and location (it doesn’t). Also at Student Research Day, Lauren Pictou presented on some her work from last summer on the snail neuroanatomy. So far, she’s found very little matching between FOUR different methods for labelling Choline Acetyltranferase (the enzyme that makes the neurotransmitter acetylcholine). All three poster posters are below!

(more…)